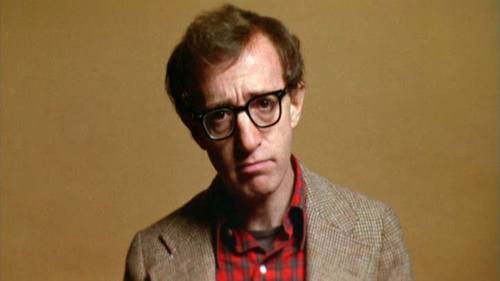

Woody Allen is one

of the most prolific directors working in Hollywood today. Having averaged one

film per year since 1969, the American filmmaker has garnered a reputation as

one of cinema’s great comedic storytellers. One of the auteur’s most prominent

thematic preoccupations is death. Allen’s fear of dying has been a recurring

theme throughout his career, to the extent that his strenuous routine has

become a distraction from the existential dilemmas of life (Lax, 2009, p. 114).

Through this essay, I will use a semiotic lens to illustrate Allen’s death

anxiety as it has evolved over the past 44 years. His career will be divided

into three stages: Allen’s “early, funny ones” (1969-1975); his more dramatic,

experimental work (1977-1999); and his lighter, more accessible films and

European travelogues (2000-present). I will examine how Allen abandoned his

slapstick roots to become a more serious, purposeful filmmaker. My overarching

stance is that Allen’s stylistic choices are influenced by his identification

as an atheistic existentialist. As most of Allen’s films are driven by dialogue

and characters, a semiotic analysis is intrinsically difficult, and I hope my

research fills a gap in the existing literature about his films.

Before dissecting

Allen’s work, it is crucial to understand that the director’s projects are

deeply personal and perpetuate their own collective ethos. While Allen has

consistently denied elements of autobiography in his films, the separation of

Allen the filmmaker and Allen the character is difficult to achieve.

Annie Hall (1977)

This is evidenced

through the opening scene of Annie Hall,

where Allen’s character, Alvy Singer, directly addresses the audience with a

monologue. Through signifiers such as “a tweedy sports jacket, a shirt but no

tie, and his trademark horn-rimmed glasses,” (Fabe, 2004, pp. 179-180)

audiences assume Allen is speaking as himself, the director. However, when

Allen says, “Annie and I broke up,” he asserts himself as Alvy Singer, the

protagonist (Fabe, 2004, p. 181). While this scene is not concerned with

biological death, it signals the metaphorical death of the author (Fabe, 2004,

p. 179). Indeed, Annie Hall was

Allen’s first attempt at making a comedic drama that appealed to the human

condition. Until then, his films were farcical comedies with parodic overtones.

However, these “early, funny” films by Allen are worth discussing as they

explore many of the themes, including death, that would characterise Allen’s

later films.

The outrageous

nature of Allen’s early comedies provided him the opportunity to reduce

existential problems to mere jokes. Death, as well as God’s silence, could be

placed in “unexpected and reductive contexts,” (Hirsch, 1990, p. 160) softening

their blow to the human psyche. Sleeper (1973)

is a science-fiction spoof about Miles Monroe (played by Allen) who is

cryogenically frozen in 1973 and revived 200 years later in a totalitarian

state. It is arguably Allen’s most visually ambitious film from his early

career.

Sleeper (1973)

In Sleeper, Miles is wrapped in aluminium

foil when he is brought out to be thawed. Aluminium foil is generally used to

cover food that we intend to eat at a later point. Here, foil is a preserver of

life, used to avoid the decay of the human body (Mooney, 2011, p. 117). Food is

a recurring theme throughout Sleeper as

it is intrinsically related to survival.

Sleeper (1973)

In one scene,

Miles continuously slips on novelty-sized banana peels. He is being felled by

that which sustains him, as “the life of the mind is interrupted by the claims

of the body.” (Hirsch, 1990, p. 160). This is Allen’s way of grappling with the

intangible, and it echoes his statement in Love

and Death that “the body has more fun [than the mind].” Allen’s slapstick

antics are a brief respite from thoughts of mortality.

Love and Death is Allen’s satire of

Russian literature, particularly Tolstoy’s War

and Peace (Lax, 2009, p. 351). Again, Allen uses comedy to undercut the

significance of death, this time by holding “vaudevillian conversations with

God.” (Hirsch, 1990, p. 160).

Love and Death (1975)

In an early scene,

Allen’s character, Boris, recalls a childhood dream where waiters stepped out

of coffins in a foggy field and danced the Viennese Waltz. This foreshadows

Boris’ later conceptualisation of nature as “an enormous restaurant,” where

animals must eat other animals to stay alive. Boris thinks of the world as a

place where he can be subsumed by forces larger than himself, including death

(LeBlanc, 1989). Here, the restaurant is stripped of its elegant connotations,

transformed into a place where only the strong survive. In Boris’ dream, there are

no people to be served, only people to do the serving. The long shot positions

the viewer to perceive the waiters as preying creatures.

Love and Death (1975)

In Love and Death, death is personified as

the Grim Reaper, dressed in a white cloak as opposed to the archetypal black.

This deviation from conventional representation reflects Allen’s framing of the

film as a comedy. By humanising death, he makes it a comedic subject. It is no

longer an abstract idea that plagues his every waking hour. In the final scene,

Allen’s character partakes in a “dance of death” with the Grim Reaper, an

obvious homage to Ingmar Bergman’s The

Seventh Seal. This scene highlights a disconnect between European and

American cinema. As Bruns (2009) writes, “The Scandinavian attitude is to take the negative seriously. Allen

takes it comically.” (p. 18). Allen’s comical treatment of death is still

an acknowledgement nonetheless. His dance with the Grim Reaper is an

affirmation that one must find enjoyment in life as a means of distraction from

the inevitability of death.

Annie Hall (1977), Interiors (1978) and Manhattan

(1979) all provided glimpses of a more focused, cinematically-conscious

Woody Allen. However, it was Stardust

Memories (1980) that would announce Allen’s detachment from his screwball

comedies of old. Stardust Memories was

Allen’s attempt to “become someone else, someone both ‘other’ and better—more

serious, more probing—than a zany comedian, a professional New York neurotic

and cutup.” (Hirsch, 1990, p. 196). Human mortality is not a major theme in the

film, but much treatment is given to the death of Allen’s comic persona that

defined his “early, funny” films. The film is shot in black-and-white, a

stylistic choice that coincides with Allen’s subdued character. Allen plays

Sandy Bates, a filmmaker who is hassled by his fans to avoid making serious

films and restrict himself to comedies.

Stardust Memories (1980)

In Sandy’s

apartment, a blown-up photograph of Nguyen Van Lem’s Vietnam War execution

hangs on a wall. The photograph mirrors Sandy’s psychological state at the

time. Like Lem in the photograph, Sandy is in a position against his will.

However, the imposing size of the photograph is a reminder that, for all of

Sandy’s pressure, he still has the privilege of being alive. One of Allen’s

recurring ideas is that life is meaningless because the universe is expanding

or decaying (Conard & Skoble, 2004, p. 9).

Stardust Memories (1980)

There’s a scene in

Stardust Memories where Sandy is

describing the impermanence of life on Earth, lamenting that “matter is

decaying.” As he delves deeper into his monologue, the camera zooms into a

medium close-up of his body, implying that Sandy is harbouring narcissistic

thoughts about the longevity of his own work. However, when Sandy says that

everything—including the works of Beethoven and Shakespeare—will perish, he

walks out of the frame and the camera lingers on a blank wall. This reflects

Allen’s philosophy that nothing lasts, and that all matter will one day

disappear. Several flashback scenes depict Sandy performing magic tricks as a

child.

Stardust Memories (1980)

One such scene

shows a young Sandy making a globe float. The globe is an iconic sign that

represents Earth. Sandy’s manipulation of the globe reflects Allen’s desire to

control the human predicament. Allen has said that “reliance on magic is the

only way out of the mess that we’re in.” (Schickel, 2003, p. 136). Ultimately, Stardust Memories is an important film

in Allen’s canon. A character in the film observes that comedians say “I

murdered that audience” when their jokes are going well, and it’s this synergy

of comedy and drama that distinguishes the film from Allen’s earlier efforts.

Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) is often

cited as one of Allen’s most balanced films. Girgus (1993) writes that it

“realizes the creative potential of all of his important films as well as the

fulfillment of a promise about his artistic values and objectives.” (p. 89).

There are several story arcs in the film, but the most relevant in terms of its

exploration of death is that of Mickey Sachs (played by Allen). Mickey is a hypochondriac

who is terrified of living in a godless universe where all human endeavour

amounts to nothing. Allen toys with the film’s chronology to heighten the

anticipation of cause and effect (Bordwell & Thompson, 2010, p. 103). We

see Mickey come into the frame with a cheerful demeanour—a drastic contrast to

the depressed man we saw earlier in the film. He recounts to a friend how a

failed suicide attempt led him to appreciate the gift of life. Through a

flashback, we see Mickey’s suicide attempt and his subsequent trip to a cinema

where he watches Duck Soup. This

scene is incongruent with Allen’s worldview that “life is inherently and

utterly meaningless.” (Conard & Skoble, 2004, p. 7). Mickey manages to

salvage some meaning from the film he is watching, concluding that life can be

enjoyable even if there is no afterlife. Allen has even conceded that he

“copped out” (Conard & Skoble, 2004, p. 125) with a convenient ending to

the film. Hence, the scene where Mickey watches Duck Soup can be construed as Allen’s attempt to escape scrutiny.

Hannah and Her Sisters (1986)

The cinema is

Allen’s comfort zone, and it is where Mickey Sachs sits transfixed to a screen

with darkness obscuring his face. In the film’s final scene, Holly (played by

Dianne Wiest) announces that she is pregnant with Mickey’s child.

Hannah and Her Sisters (1986)

As both characters

embrace, we see them reflected in a mirror. The mirror forces the audience to

question the reality of the moment (Bailey, 2001, p. 114). It may also be

Allen’s way of examining his own, and Mickey’s, place in the world. As someone

about to venture into fatherhood, Mickey must determine whether he is fit for

the role. The prospect of fathering a child may allay his fears of dying without

a legacy.

Deconstructing Harry (1997) stands as

one of Allen’s most personal films. If Stardust

Memories was Allen’s response to an audience that wanted nothing but to

laugh, Deconstructing Harry is his meditation

on the struggle of dramatic writing—of separating art from the artist. Allen

plays Harry Block, a writer who uses the people around him as inspiration for

his novels, much to their chagrin. Harry interacts with these characters in

fantastical sequences, where they appear not so much as people, but as phantoms

of Harry’s past. Indeed, this detachment from human feeling has inspired the

idea that the characters in the film are “corpses and vampires of lost love and

life.” (Girgus, 2002, p. 165).

Deconstructing Harry (1997)

This notion of

characters who cannot realise their human agency is apparent from the opening

scene, where Lucy (played by Judy Davis) arrives at Harry’s apartment via taxi.

This scene is repeated several times to the point that it resembles a technical

glitch. This scene echoes Stephen Heath’s observation that film “depends on

that constant stopping for its possibility of reconstituting a moving reality.”

(Girgus, 2002, p. 165). The monotonous repetition of Lucy’s entrance emphasises

her deathly existence, whereby she serves as Harry’s plaything.

Deconstructing Harry (1997)

In one surreal

scene, Harry takes an elevator down to Hell. Instead of elevator music, we hear

a voice informing us that Hell has several levels—each one reserved for people

who have committed various transgressions. The people in Allen’s Hell indulge

in hedonistic pursuits as jazz music plays in the background. It is evident

that Allen does not conceive of Hell as “eternal punishment after dying.”

(Girgus, 2002, p. 166) To him, existence is

hell. He is surrounded by people who have become nothing but fodder for his

creative output, which will ultimately perish when he dies.

Since 2005, most

of Allen’s films have been European productions. Allen finds it is convenient

to shoot in Europe because he can secure favourable financing deals (Lax, 2009,

p. 163). Allen, now in his 70s, has experimented with different genres and

styles. He now feels a greater sense of creative control, but may feel slightly

reticent about his age and longevity as a filmmaker. Match Point (2005) revisits a theme that was addressed by Allen in Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989)—namely,

that a godless universe means crime will go unpunished. Allen has said that he

wanted to explore murder in a philosophical context so Match Point wasn’t reduced to a “genre piece.” (Lax, 2009, p. 24).

Match Point (2005)

Allen rejects the

conventions of a traditional crime film, choosing not to show the murders

committed by the protagonist. Chandler (1997) writes, “Semiotically, a genre

can be seen as a shared code between the producers and interpreters of texts

included within it.” Thus, Allen’s deviation from the codes of the crime genre

forces his audience to consider the philosophical implications of murder. The

protagonist, Chris, murders two people without being punished. The nature of

the film medium results in the audience’s complicity with Chris’ crime. Viewers

can only watch and silently condemn his actions. Any attempts to intervene are

as fruitless as God’s.

Match Point (2005)

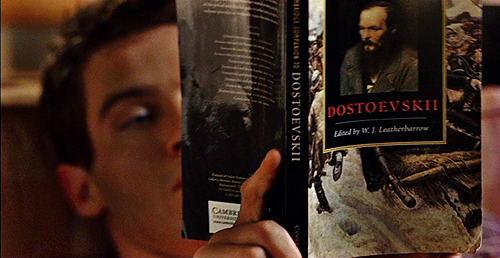

In one scene,

Chris is shown reading Dostoevsky’s Crime

and Punishment. The protagonist of the novel also commits a murder in the

belief he will go unpunished. Chris puts

the novel down and picks up The Cambridge

Companion to Dostoevsky. The novel has mimetic power (Hall, 1997, p. 24) in

that it represents aspects of human nature. The study guide, on the other hand,

is a synthesis of theories. Chris’ dissatisfaction with the novel reflects

Allen’s worldview as an atheistic existentialist. Unlike Dostoevsky, he does

not believe in the redemptive power of guilt (Siassi, 2013).

To Rome with Love (2012) provides

insight into Allen’s anxiety over death and ageing. It marked Allen’s first

acting role since Scoop in 2006—a

possible indication that he equates acting with living. To remain off-screen

would result in the death of the “Woody Allen character” he has maintained

since he began starring in his own films. In one scene, Monica (played by Ellen

Page) marvels at how Rome was once a magnificent civilisation, but now stands

as a collection of ruins. She calls this realisation Ozymandias Melancholia—the sinking knowledge that nothing ever

lasts.

To Rome with Love (2012)

This is contrasted

with the following scene, wherein Monica and Jack walk inside a modern

auditorium—a place of artistic output. Jack says his ambition is to “build

radical structures” and “change the architectural landscape.” An extreme long

shot is used to emphasise the inferiority of Monica and Jack to their

surroundings. This resonates with Allen’s philosophy that the artist’s

productions are futile to the ravages of time. An artist cannot live through

their work.

Fundamentally,

Woody Allen’s atheistic beliefs have shaped much of his cinematic output. While

Allen’s films are indeed driven by dialogue and character development, the

director symbiotically blends cinematic codes and conventions with his ideas. Allen

considers death to be the enveloping force that renders all human endeavour

meaningless. His films explore both the cessation of life and the metaphorical

‘death’ of characters and ideas. Despite the significant longevity of Allen’s

career, he has managed to remain consistent in the views he espouses. Even his

earliest films, which were ludicrous farces, contained glimpses of Allen’s

cynical worldview. As he became more philosophical in his filmmaking, Allen

explored themes such as the transience of the universe, the separation of art

from the artist, and freedom from punishment in a godless universe.

References

Allen, W. (Director).

(1973). Sleeper [Film]. Beverly

Hills: United Artists.

Allen, W.

(Director). (1975). Love and death [Film].

Beverly Hills: United Artists.

Allen, W.

(Director). (1977). Annie hall [Film].

Beverly Hills: United Artists.

Allen, W.

(Director). (1980). Stardust memories [Film].

Beverly Hills: United Artists.

Allen, W.

(Director). (1986). Hannah and her

sisters [Film]. Los Angeles: Orion Pictures.

Allen, W.

(Director). (1997). Deconstructing harry [Film].

Los Angeles: Fine Line Features.

Allen, W.

(Director). (2005). Match point [Film].

London: BBC Films.

Allen, W.

(Director). (2012). To Rome with love [Film].

Milan: Medusa Film.

Bailey, P. J.

(2001). The reluctant film art of Woody Allen. Lexington, Ky.:

University Press of

Kentucky.

Bordwell, D.,

& Thompson, K. (2010). Narrative as a formal system. In Film art: An

introduction (9th ed., pp. 78-116). New York. NY: McGraw Hill.

Bruns,

J. (2009). Loopholes: Reading

comically. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers.

Chandler, D.

(1997). An introduction to genre theory. Retrieved

from http://www.aber.

ac.uk/media/Documents/intgenre/chandler_genre_theory.pdf

Conard, M. T.,

& Skoble, A. J. (2004). Woody Allen and philosophy: You mean my whole

fallacy

is wrong?. Chicago: Open

Court.

Fabe, M. (2004). Closely

watched films: An introduction to the art of narrative film technique.

Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Girgus, S. B.

(1993). The films of Woody Allen. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Girgus, S. B.

(2002). The films of Woody Allen (2nd ed.). Cambridge:

Cambridge University

Press.

Hall, S. (1997).

The work of representation. In

Representation: Cultural representations and

signifying practices (pp. 15-64).

London, UK: Sage in association with The Open University.

Hirsch, F. (1990).

Love, sex, death & the meaning of

life: The films of Woody Allen. New York:

Proscenium

Publishers Inc..

Lax, E. (2009). Conversations with Woody Allen: His films,

the movies, and moviemaking:

Updated and expanded. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

LeBlanc, R. D.

(1989). “Love and death” and food: Woody Allen’s comic use of gastronomy.

Literature/Film Quarterly,

17(1), 18.

Mooney, T. J.

(2011). Live forever or die trying: The history and

politics of life extension.

Bloomington: Xlibris

Corporation.

Schickel, R. (2003). Woody Allen: A life in film. Chicago:

Ivan R. Dee.

Siassi, S. (2013). Forgiveness in

intimate relationships: A psychoanalytic perspective. London:

Karnac Books Ltd..

No comments:

Post a Comment